10 June 2016

“In over fifty years of activity, Jeanne-Claude and I have realized only 22 of the 59 works that we conceived, owing to the difficulty of obtaining permits. While we have lost interest in some of the unfinished projects, there are others we still care deeply about: The Floating Piers is one of these.” More than six years have passed since his wife’s death, but Christo, whose full name is Christo Vladimirov Yavachev, speaks as if she were still at his side. At the end of 2009, Jeanne-Claude was carried off suddenly by a brain aneurysm, interrupting a long human and professional partnership. But Christo has not given up and has continued to fight to realize the works they conceived together. The last of which will be unveiled on June 18 at Lake Iseo. The Floating Piers is a system of walkways that will embrace the island of San Paolo and part of that of Montisola, uniting them to the mainland (the route begins from the town of Sulzano). A path running just above the surface of the water for more than three kilometers that will be open to the public day and night for three weeks and temporarily change the lake’s appearance. Owing to the impact they have on public spaces, the projects of the pair of land artists usually take a long time to put into effect. Wrapping the German Reichstag (1995) and the Pont Neuf in Paris (1985) or scattering gates of colored fabric around New York’s most famous park (2005), were not simple operations to carry out. They required masses of bureaucratic permits, as well as a sound plan of engineering. “All artists would like their art to be talked about. Our works are the only ones capable of getting people doing it before they are created,” jokes Christo when we meet him on the terraces of a hotel at Lake Iseo. The 81-year-old artist speaks English with a strong East European accent. He is an American citizen and has been living in New York for over forty years, but his Bulgarian origins still color his voice. Dressed in jeans, windproof jacket and gumboots, he has just returned from a boat trip to check the progress of the work on his new installation. He appears satisfied. This time he has done it all in just two years, breakneck speed by his standards. A result achieved thanks to his long-standing ties with the Italian art world, and a little luck too.

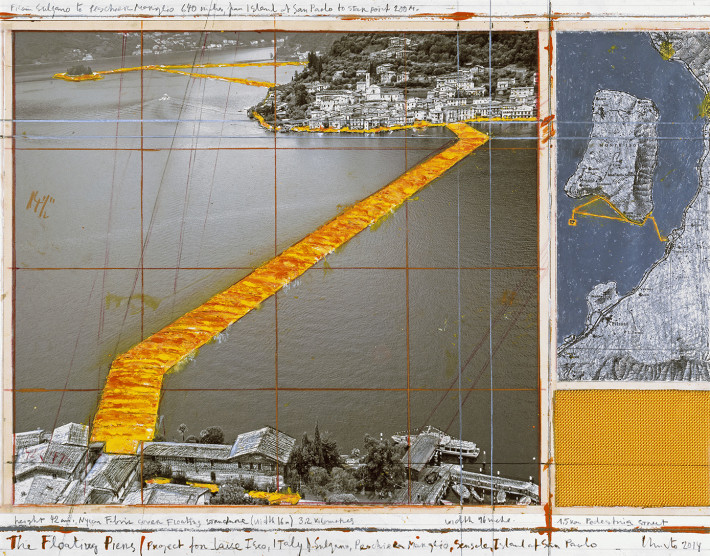

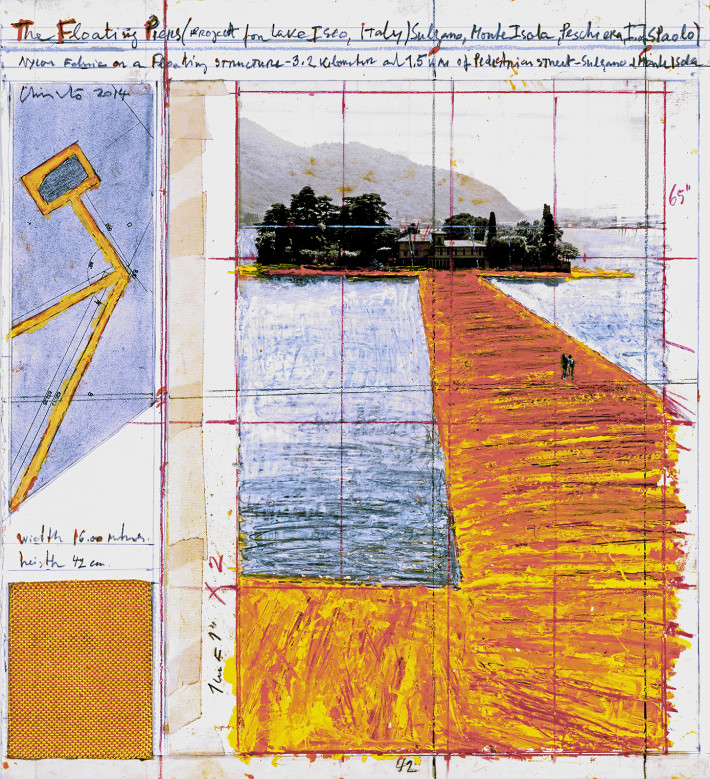

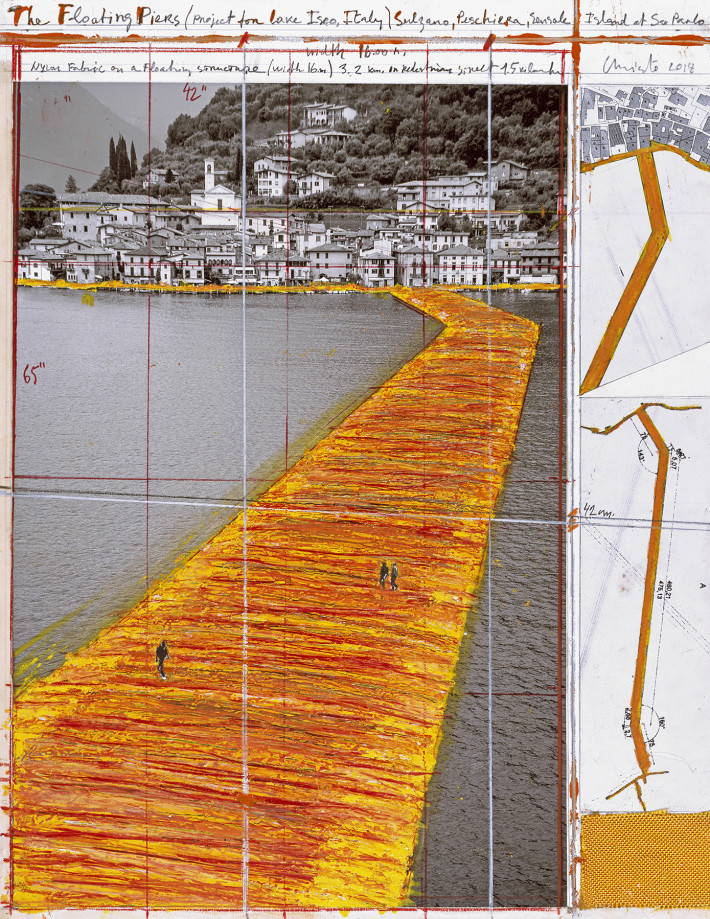

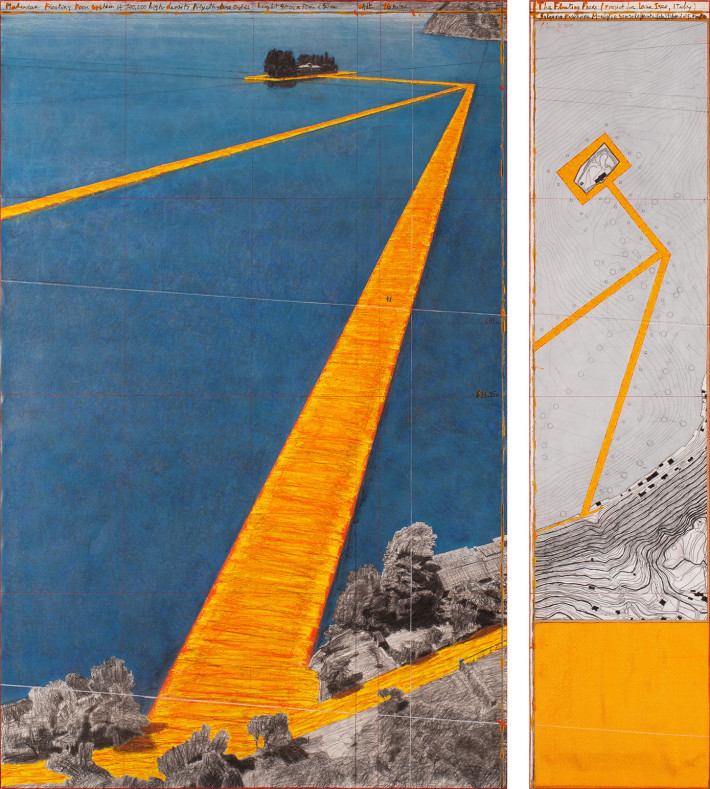

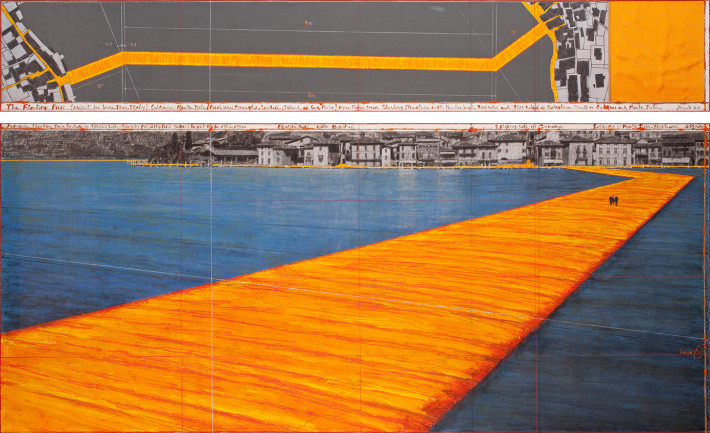

Christo, The Floating Piers, 2014. Drawing. Photo: André Grossmann.

How did you manage to complete the installation in such a short time?

You always need a bit of luck and this time we had a lot. I knew I had to obtain permits from four main parties: the president of the authority responsible for the catchment area, the mayors of the two municipalities involved—Montisola and Sulzano—and the owner of the island of San Paolo. I have known the critic Germano Celant for many years and I asked if he could give me a hand. We began with the private island, which is the property of the Beretta family. Franco Beretta immediately showed enthusiasm for the plan and helped us to make contact with the local authorities. As soon as I turned up for the appointment, I realized that the president of the catchment area authority, Giuseppe Faccanoni, was the right person to support The Floating Piers. He had studied in New York, knew my work and had seen the installations I made in Milan in the seventies. He comes from enlightened stock, related to Vladimir Nabokov. His ancestors designed the first modern sewage system in Habsburg Vienna and built the finest villa in the art nouveau style on the lake. If it hadn’t been for him, I would probably have never succeeded in completing the project.

Christo in his studio making preparatory drawings for The

Floating Piers. New York, November 2015.

Where did the idea of The Floating Piers come from?

Some interventions were conceived for a specific site—Wrapped Reichstag for the parliament in Berlin and Surrounded Islands for the islands in Miami’s Biscayne Bay, for example. Others, however, can be adapted to different places, as was the case with Wrapped Coast, where we settled on an expanse of the Australian coast, and Valley Curtain, which saw us stretching a giant piece of orange cloth between two mountains in Colorado. The Floating Piers belongs to this second category: we had the idea in 1970 and the first failed attempt to realize it was in the delta of the Rio de la Plata, in front of Buenos Aires. The design was the same, except it entailed the creation of fixed piers covered with fabric: at the time it was not yet possible to have them float, or at least it was technically very difficult. In 1997 we tried again in Japan, in Tokyo Bay. We worked on it for two years amidst a thousand difficulties with the local authorities. In the end Jeanne-Claude lost her patience and we dropped it. In 2014 I started working on two projects, Over the River in the US and The Mastaba at Abu Dhabi. Nine years had passed since the time when we had finished out last work, The Gates in Central Park. We had gone on investing energy and money to go ahead with the two projects, without success. One day, while I was traveling from Basel, where I have a place in which I store works of art, I said to myself: that’s enough, I want to realize at least one more work while I’m still alive. And I thought that perhaps I would be able to construct The Floating Piers in Italy. Before emigrating to the United States, Jeanne-Claude and I spent a lot of time here. We made three installations, at Spoleto in 1968, in Milan in 1970 and in Rome in 1973. We played a leading part in various exhibitions, we knew curators and gallerists. I liked the idea of going back to Italy and hoped to get a better welcome than in the United States or the Arabian peninsula. This is what convinced me.

Christo, The Floating Piers, 2014. Drawing. Photo: André Grossmann.

Why did you choose Lake Iseo?

I knew the lake from the sixties. I came to make an inspection in incognito, telling everyone I was going to my depository in Switzerland. The presence of Montisola has been fundamental. It’s the highest lake island in Europe, inhabited by almost two thousand people, and is only connected to the mainland by a ferry. The idea of linking them to the shore with a pier fascinated me. Then there is the topographic factor, which offers the possibility of viewing the installation from different heights. And its proximity to Milan and Venice, which makes it easily accessible from abroad too. And then, as I said, there was the hope of obtaining permits in a reasonable amount of time.

Even though Italian bureaucracy is certainly not known for its rapidity.

Yes, but I have good friends in Italy, I knew I would be able to count on them. Before I mentioned Germano Celant, whom I’ve known for more than fifty years: he assisted me and was wise enough to keep the project secret till the end. I think this helped us to avoid snags and to speed up the process. Luck and contacts are fundamental, but this is true everywhere, not just in Italy. I started to ask for permits to wrap the parliament in Berlin in 1971. The key to obtaining authorization was to convince the speaker of the Chamber, that is to say the master of the house. I had to wait for the election of six different speakers before getting the right support. Something similar happened in New York too with The Gates, which was turned down twice, in 1979 and 1981. In the mid-eighties, we made friends with a businessman who had just founded a small agency specializing in financial news. It was only when this person became mayor of New York that we were finally able to realize the project. He was Michael Bloomberg.

Christo, The Floating Piers, 2014. Drawing. Photo: André Grossmann.

What difficulties did you have to overcome to go through with The Floating Piers?

Our works are unique. This means that, technically, we never know how we are going to realize them in advance. Usually this is how it goes: I start to dream and make drawings in my studio in Manhattan, then we assemble a team of technicians to evaluate the feasibility of the project. In this case we hired an engineering company that drew up a document of over 100 pages with which to obtain the permits. The piers are formed from over 200,000 floating plastic cubes, covered with 70,000 square meters of an iridescent yellow fabric (reinforced nylon) and anchored to the lake bottom with 170 weights of 5 tons each. The covering is wider than the pier: as a result the edges of the fabric float on the water, producing a disorientating effect. The work is very tactile, it has not been made just to admire from a distance and the best way to experience it is to walk on it in bare feet. And to find this out we had to do some trial runs. In order to do this away from prying eyes, we rented a small private lake on the border between Germany and Denmark. There we mounted an actual-size pier to test the proportions and the materials. I chose a nylon that changes color in relation to the light and the humidity. And to make sure that the structure was strong enough, we drove over it with an off-road vehicle.

Christo, The Floating Piers, 2015. Drawing. Photo: André Grossmann.

How much does an operation of this kind cost?

Around 15 million euros, but to this question Jeanne-Claude would have responded: who can say exactly how much it costs to raise a child? What is certain is that all our interventions are self-financed through the sale of preparatory works like paintings, drawings and sketches. We have never accepted commissions or sponsorships of any kind because we want to have complete control over what we do. All our works have a purely aesthetic value. They are only necessary for me and Jeanne-Claude.

The use of cloth to wrap, cover or mask spaces and structures is a constant feature of your work.

Cloth is an element that clearly conveys the nomadic character of my projects. It can be installed in situ in a short space of time, just as nomads do when they put up their tents and settle temporarily in a place. Fabric is also a fragile and primordial element, like an extension of our skin. And it has a sensual character that transmits a certain magnetism.

Are you still planning new installations or concentrating your energy on completing old projects?

I don’t have a precise plan, I try to be spontaneous. Before getting caught by the whim of realizing The Floating Piers I was focused on Over the River and The Mastaba. The former entails covering a stretch of the Colorado River with a suspended piece of fabric, while the other aims to create an enormous sculpture out of crude oil barrels in the desert of Abu Dhabi. The plans for those two projects are so detailed that they could be finished even if I were to die in an airplane crash tomorrow.

Christo, The Floating Piers, 2016. Drawing. Photo: André Grossmann.

The collaboration with your wife dates back to 1961. How does it feel to work alone now?

It’s very difficult, Jeanne-Claude is always in my thoughts. I lived and worked with her for over fifty years. It has been an immense loss. We met in Paris when we were both 23 years old and never separated after that. She became an artist out of her love for me. She always said that if I had been a dentist she would have become one too. For me she is still alive, she is part of my work.

Is there something that you miss in particular?

Her critical sense: we used to discuss things and exchange ideas continually. I miss her sense of humor too. During one of the many meetings we held to present Over the River to the public and listen to the objections of local residents, a woman told us that the poles set in the ground to suspend the fabric above the river would certainly have caused an earthquake. Obviously this was an absurdity, but at the end of the debate Jeanne-Claude was delighted because she could say that she was the only woman in the world capable of creating an earthquake.

Artists tend to have a fairly strong ego. Was there never a moment in which you ran the risk of suffocating one another?

No. Everything we did was aimed at completing our work. The ego was in the work itself. Succeeding in realizing it in a public space, involving a lot of people, is such a great satisfaction that none of the rest matters.

Aerial view of the project’s building yard on the Montecolino peninsula (right) and the temporary storage on lake Iseo (left), April 2016. Photo: Wolfgang Volz.

Workers push one of the frames underneath a floating element before connecting it with screws, April 2016. Photo: Wolfgang Volz.

Christo, 2016. Photo: Wolfgang Volz.

Christo, The Floating Piers, 2016. Photo: Wolfgang Volz.

Christo, The Floating Piers, 2016. Photo: Wolfgang Volz.

Christo, The Floating Piers, 2016. Photo: Wolfgang Volz.

Christo, The Floating Piers, 2016. Photo: Wolfgang Volz.