20 September 2013

In response to great demand, we have decided to publish on our site the long and extraordinary interviews that appeared in the print magazine from 2009 to 2011. Forty gripping conversations with the protagonists of contemporary art, design and architecture. Once a week, an appointment not to be missed. A real treat. Today it’s Markus Miessen’s turn.

Klat #03, summer 2010.

Markus Miessen is someone who is brave enough to say, without mincing his words, that democracy and participation, as we know them, should be dispensed with. He tells you why and he is persuasive: mandates, mediations and consensus are simply ways of withdrawing the responsibility from individuals. Miessen proclaims a proactive engagement, a direct action: in politics, in architecture. We met him to explore thoroughly this bold and controversial idea of his.

I have heard you say more than once “avoid democracy at all costs.” Obviously, being German and an advocate of participation, your position becomes polemic and controversial. Is this the point?

On the one hand, it is certainly intended to stir a debate about current practices. On the other, it refers to a sometimes problematic politics of non-critical inclusion. Since the mid-nineties, participation has become increasingly overused. We are led to believe that everyone can take part, everyone can participate in the decision-making process, when in fact, in many political systems, participation is merely an excuse for elected politicians to withdraw from their assigned responsibility. This situation could be described as Harmonistan: an illusory state in which the public is deluded into believing that one can always be involved in the transformation of reality. The situation is, in fact, the reverse: while everyone has been turned into a participant, the uncritical and romantic use of the term – hijacked and supported by a repeatedly nostalgic veneer of worthiness, phony solidarity and political correctness – has become the default mode of politicians to withdraw from accountability. This can be traced back through several Labour governments, most prominently New Labour in the UK, and the notion of the consensual Polder Model in the Netherlands. When I claim that sometimes democracy has to be avoided at all costs, what I really mean is that we have to rethink the prevailing notion of participation. Instead of reading participation as the charitable savior of political struggle, I propose a reflection on the limits and traps of its real motivations. Instead of breeding the next generation of consensual facilitators and mediators, I am arguing for conflict as an enabling, productive rather than disabling, force. It presents a format and practice of “conflictual participation,” which is no longer understood as a process by which others are invited into something, but as a means of acting without mandate, as an uninvited irritant: a forced entry into fields of knowledge that can arguably benefit from external thinking.

Studio Miessen, Winter School Middle East 2008/09. Poster design: Zak Kyes

This position is evidently informed by your work with Eyal Weizman, who founded an entire body of work based on the notion of “spatial tactics,” and who also introduces your new book. And while this notion of conflictual participation sounds, in theory, all well and good, can you give us an example of where it has been invoked as an instrumental or effective agent of change in practice?

Eyal is my PhD mentor and, yes, he has certainly been an inspiration in terms of my practice. But there are many others I would also consider as influential from other fields, such as Christoph Schlingensief or Josef Bierbichler in theatre, or Cedric Price in architecture. My theory of praxis is not so much about conflict per se, but to reverse the notion of participation into a pro-active engagement of the individual, self-initiated practitioner. This is, by default, very different from the role of an agent, who necessarily represents the cause of others and, hence, acts and practices with a clear mandate. I am promoting a practice without mandate, and a project in which I am currently really trying to push this agenda forward is the Winter School Middle East, a self-initiated small-scale nomadic educational framework, which I set up in Dubai in 2008. This year, it moves on to Kuwait, to be followed by Tehran in 2011. The Winter School is dealing locally with issues of critical spatial practice. In Dubai we investigated the Labour Camps, in Kuwait this year we run a research project on Bedouin housing agglomerations, in collaboration with UN-Habitat. Regarding your question of conflictual participation, a good example is a consulting project I am working on with Andrea Phillips, where we, as outsiders, enter the institutional interior of the Dutch organization SKOR, in order to critically question, advise, and help redesign their institutional framework and policy.

Your latest book The Nightmare of Participation completes the participation trilogy. We could call you “participation man”… In the last years, participation has become a catchword in art and architecture, in many ways perpetuated by your first publication Did Someone Say Participate? Yet, within architecture one could argue that participation is a long-standing tradition, going back to the fifties and sixties with groups like CIAM, that with their practice marginally dealt with the basic architectural process. How is your use and invocation of the term different?

Instead of advocating, I revoke. Participation-addicted romantics that still believe in a united struggle may despise me for this, but I believe the only way out of the crisis is to become a pro-active individual and to no longer rely on conventional participatory frameworks. One has to take action into one’s own hands. Of course, in architecture there were groups such as CIAM, and their efforts and tasks are highly commendable. However, their premise is based on the belief that inclusion will produce a surplus. I am no longer sure whether this is always the case. What I attempt to introduce in my recent work is the notion of Crossbench Praxis. This approach is modeled onto the independent politicians in the House of Lords, in the UK. Although the House of Lords is a highly problematic and deeply conservative construct of representation, the abstract position of it, and especially the crossbenchers, is interesting to hijack. They do not belong to a specific party (i.e. Conservatives or Labour), but generate their decisions based on their individual judgment, outside the consensual realities of an existing party. My term Crossbench Praxis encourages a disinterested outsider and uncalled participator, who is not limited by existing protocols, but enters the discursive arena with nothing but critical intellect and the will to generate change.

Could we say that your approach goes in the direction of a new practice, in which architecture, before being about raising buildings, is about thought and mediation processes? Could one even go so far as to say that this sort of disciplinarity, which comprises spatial advising and mediation that works across discourses – among politicians, policy makers, economists, cultural advocates, artists, developers – is a new form of architecture?

I don’t know if I am indicative of a new type of practitioner, but what I agree on is that thinking through and the production of non-physical realities and identities co-produces a physical reality that cannot be negated. Architecture is about relationships, politics and identity. This can also be produced through a piece of writing – an essay in a newspaper or magazine can change the entire perception of an urban area – and, as a result, force and propel a development of migration. In contrast to many architects, the physical dimension is not the application, but rather the testing of a hypothesis. The range of projects definitely plays an important role in the production of an reality, which is far from building, but allows for a production of opinions that alter reality. Our current projects are ranging from small-scale domestic interiors to galleries to institutional buildings, strategic frameworks for urban areas and the production of future identities of regions, in Austria for example. The way we approach an architectural project is based on the same logic with which we approach a strategic framework design. We are not interested in primarily formal characteristics, but in the development of content-driven realizations of practice in three-dimensional space. One could of course argue that this has always been part of architecture and spatial practice.

Toute la Memoire du Monde, 2009. Archive Kabinett, Berlin. Spatial design by nOffice. Photo: Chiara Figone

Is your book about this approach?

The Nightmare of Participation attempts two things: on the one hand to argue for a reverse understanding of participation from the passive consensual and politically correct follower to the pro-active practitioner, and on the other to engender and push for a post-consensual practice. One that is no longer reliant on the often ill-defined modes of operating within politically complex and consensus-driven parties or similar constructs, but instead formulates a necessity to undo the innocence of participation.

What is your fascination with conflict?

I am very much interested in the notion of the agonistic model of democracy, proposed by political theorists Chantal Mouffe and Bonnie Honig. Chantal insists on the dimension of the political as something that is linked to the dimension of conflict that exists in human societies. Her reading translates into a notion of democracy in which a form of consensus beyond hegemony, beyond sovereignty, will always be unavailable. The tail end of the nineties was a period of buzzwords: sustainability, participation, democracy, the multitude. This was happening across the board, beyond political alliances, whether on the left or on the right. At some point, it became sexy to subscribe oneself according to one of those terminologies, whether or not one was convinced about its content or possible future potential. But the whole point about cultural praxis is of course that it presupposes and assumes possible futures, that it speculates on what might be possible through a series of critical theories and practices that for society at large are still too abstract. Such an approach, by default, will be conflictual. This was also the primary reason for me to start the trilogy with the question Did Someone Say Participate?, which later was released as a volume co-edited by Shumon Basar.

In the past you were a competitive snowboarder. And you once showed me a video about an impromptu project for a ski-jump kicker: completely frivolous and completely fabulous at the same time! Built into the project was extreme fun and extreme temporality. Are these two things part of your work?

There is certainly a serious interest in temporality in our work. Hence, there is also an interest in finding fun in what one is doing. Architecture is the most snafu, god-awful job in the world; at the same time it is arguably one of the most interesting. Without a certain optimism, relentless belief and fun in what one is doing, the “project” of architecture would simply be an impossible task. When I was more involved in snowboarding, the whole point about building a kicker had to do with the potential of producing something that both within its environment and within the practice of freestyle snowboarding would be able to create an unprecedented matter. This, of course, was related to the aspect of fun, but – translated into spatial practice – I think it still holds true, as it is based on a belief in relevance. The issue of temporality and space is also something I will explore in my new role as professor at the Hochschule für Gestaltung (University of Arts and Design) in Karlsruhe, where I will be dealing with the notion of archival practices in space, modeled onto and through the project that nOffice is developing together with and for Hans Ulrich Obrist in Switzerland.

One of your first and I would say pivotal projects in which temporality entered into the plan, was for the Kunsthalle in Cologne. How does temporality enter into your work now, as for example, in your most current submission for Performa Biennial (2009) in New York City?

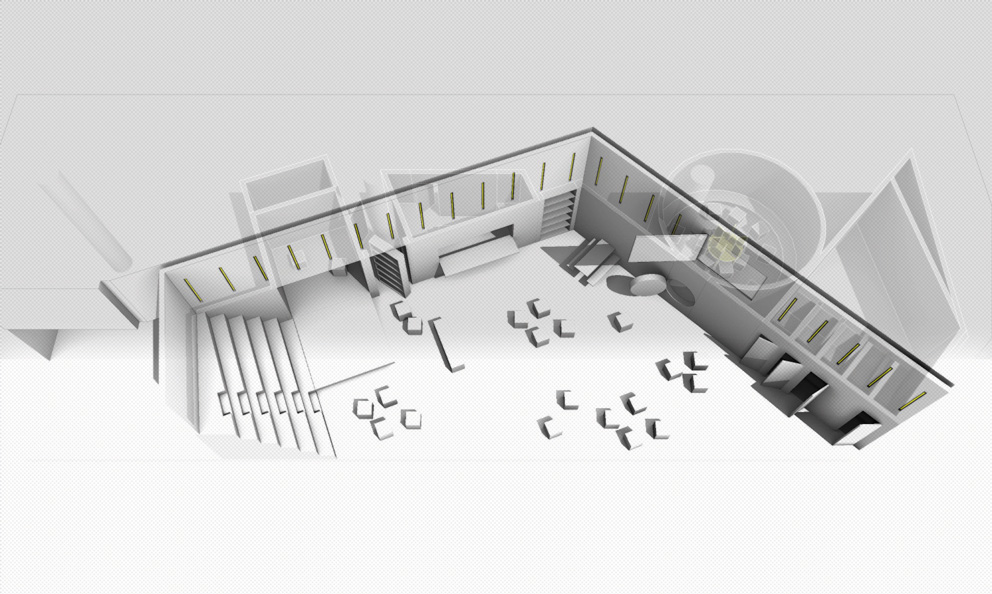

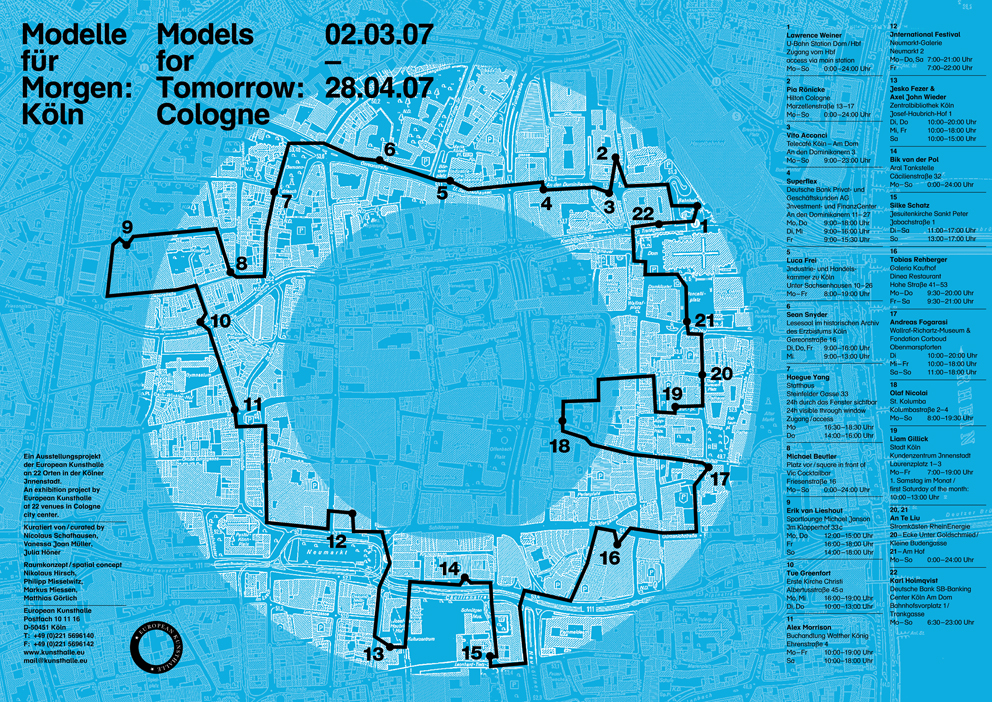

Temporality is both a means and an alternative understanding of practice. In the European Kunsthalle project it was all about decentralizing an institution, while producing a set of alternative and unexpectedly activated post-public spaces across the city of Cologne. This project was done in collaboration with Nikolaus Hirsch, Philipp Misselwitz and Matthias Görlich. The task for nOffice’s Performa Biennial Hub (New York), in many ways, was the reverse: to generate a centralized urban space for a decentralized institution, which needs to find a place in which it can communicate its main thesis and consolidate an audience. The question of temporality is always crucial when speaking of spaces that are organized and defined by a specific temporal agenda. We are now also working together with Bassam El Baroni and Jeremy Beaudry on an architectural project for one of the venues of Manifesta 8 in Murcia, which will be dealing with this aspect of programming and space.

The saying goes that architecture is a way of life. Would you say this is an outmoded cliché? For example, you have a fabulously and meticulously organized library, and whenever I see it I can’t help thinking that your project of the archive as an architecture of knowledge somewhat starts at home, quite simply with your love of books.

Yes, I would agree with you, in that on the one hand architecture could be described as a way of life, while, on the other hand, it should absolutely be understood as an outmoded cliché. Its professional conduct forces you to always be 150 percent on board, while its slightly romanticized reality forces you to look out for other, secondary opportunities. The profession is certainly not one to be recommended if you want to practice architecture within the remit of criticality, rather than that of corporate service provision. It is true that between Studio Miessen and nOffice we share the obsession with archives and libraries, and have built up specific expertise in terms of imagining and designing them. My own library could maybe be described as a proving ground for organizational principles: how to deal with physicalized knowledge, through the medium of printed matter, in space.

Do you think signature in architecture is out-moded? Does your practice with nOffice argue for this and, for example, stand in a somewhat polemical position to practitioners who are ten to fifteen years older than you are? If so, how do you hope to be recognized? I ask because whereas the signature photo for older architects is the object or the building, the signature photograph for you seems to be the meeting or the discussion.

Signature will always prevail in architecture. Most architects are longing for a singular, recognizable spatial language that can be understood, replicated and consumed. I am not sure whether this is out-moded, it is simply a reality and will continue to exist and be produced. There is no point in opposing to the practices of those who are fifteen years older than us. They have their way of approaching practice and we have ours. I think that eventually we will be recognized simply through a different approach in terms of content. In the long run, clients will understand that there is a difference between solutions that are simply the result of a pre-set personal agenda and those that are custom-built onto the structure of their concerns. And yes, I would very much agree on your reading of our approach as being based on a set of requirements which emerge through discussion and direct engagement.

You are known for producing quickly and for the notion of authorship subsumed within the editorial text or book, or as a sort of testing ground. There are others models, particularly in the States, for example, that still advocate the author as the sole individual, and writing as the painstaking endeavor of a solitary practice.

Yes, we like to produce quickly, as we believe that there is something about intuition that should not be underestimated. We consider our products as test cases, regardless of whether they are book, building, exhibition or strategic framework. However, as we are very interested in the notion of collaboration and inquiry, not all projects can come to a result equally quickly. We are certainly not stuck with the notion of individual authorship, although this, in some projects, can make things easier. Our practice entails a desire for conflictual dialogue and dispute with third parties.

nOffice, Performa Biennial Hub, 2009, New York. Photo: Paula Court

What is the importance of your books in your architectural practice? Do you see these as works of architecture? Do you use them as places of experimentation? How do you imagine they could reach beyond the architectural community?

I am not sure whether to call my books a work of architecture. However, they could be described as the backdrop of an architectural project, which is concerned with the tracing of individual voices in the production of space. My books are intended to produce a parallel reality with regard to the practice of nOffice. They are geared towards the stimulation of discussion and debate, a cross-fertilizer in the production of an alternative spatial understanding and knowledge. Spatial theory and practice will always be a niche. However, I am attempting to reach audiences beyond the architectural community by using alternative means of distribution – when it comes to books – and by publishing in a wide range of print-media, which ranges from academic to popular culture, from urbanism journals to pop music magazines and daily newspapers.

The architectural profession is plagued with projects that don’t go forward and that quite literally don’t pay. Is there hope?

Well yes, I hope. If I were not optimistic, I would do something else.

One of the most blatant perpetrators of exploitation within the discipline is the educational institution itself.

The phenomenon of education becoming a market economy is probably best exemplified by the Rotterdam-based Berlage Institute. Within a few years, the school has deteriorated from a once-challenging hub for critical thinking and extra-disciplinary production into what could be described as an industry-led environment in which teaching is only granted to those professors who bring in more money than they are paid to teach their students. Such a framework is coupled with a series of double standards. What is the value of a publicly funded institution that only caters to the industry, while attempting to generate profit through the politics of employment? Their agenda is simple: more money. Pedagogy comes later. The professor’s role has been turned into that of an administrator, an institutionalized manager for the client, someone who is expected to contribute to the academy his or her personal and professional contacts and clients, and to control a certain amount of volunteer workers, the students. In such a context, students that are paying twenty five thousand Euros for a two-year program are being misused to deliver free labor to corporate clients, only for the institution to secure its existence. This evidently has an effect on the way that professors teach. Reviews of student work are used as presentations for the clients.

You are working on a project with Hans Ulrich Obrist and Armin Linke. Can you tell us something about it?

The project is dealing with the realities and post-production of Hans Ulrich’s private archive. nOffice is currently working on a spatialization, organizational structures and design for the archive, as well as a physical design for the library, residency and summer academy. According to the notions supplied by Hans Ulrich’s twenty-five years of endeavour.

I have often joked about you becoming a sort of cultural minister, later in life. Could you explain what you see this sort of role to be, and why a position like this might be needed in Europe or in Germany?

I would certainly not mind. I can’t speak for Europe per se, but in Germany there is certainly a need for critical practice to be fostered beyond the sometimes harshly conservative and consensual decision-making in the formalized cultural sphere.

Art and Architecture, is this a tired relationship or one you still find interesting, particularly given the fact that you seem to shuttle between these worlds?

Art and Architecture is interesting, but so are Art and Science, Architecture and Politics, or many other such couples. The simple coupling of the terms does not necessarily produce anything. Personally, the only thing I find interesting about the relationship between Art and Architecture is that, for an architect, it is quite likely to find people in the art world who are interested in debate: you don’t have to start from scratch, if you know what I mean. However, one thing I don’t like about either of those worlds is their hermetic exclusivity. This goes hand in hand with the fact that there are probably not many other disciplines or environments in which practitioners prostitute themselves to such degree.

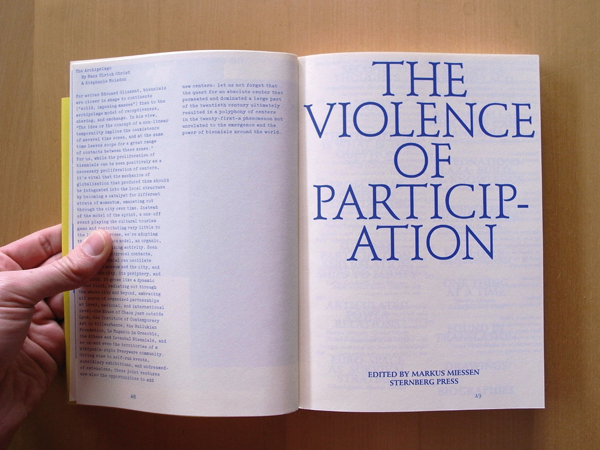

Markus Miessen, The Violence of Participation. Sternberg Press, 2007. Photo: Zak Kyes.

The exhibition, as a typology, has been described as an area of experimentation, as a testing ground with a certain ethics. I argue in my forthcoming book for something more than this, that the exhibition as architecture is tied to a certain responsibility, which must do more than represent. What do you think about it?

The exhibition is the space in which the thinking about and the production of new discourses is being negotiated.

How would you say the notion of economy plays into architecture?

The first thing that comes to mind is that while architecture is one of the most expensive commodities, architects are notoriously underpaid. The second is that one should critically consider scale and its relevance. Often, architects are tackling issues with ineffective or non-relevant scales or tools, just simply because they feel the urge to build.

You have two parallel strands of practice going, Studio Miessen and nOffice with Ralf Pflugfelder and Magnus Nilsson. Can you describe the relationship between them, where they intersect and diverge, and the strategy behind working in two parallel worlds?

When I started Studio Miessen, I had lost all belief in the architecture world, specifically the discipline of building. A few years later, Ralf Pflugfelder and Magnus Nilsson convinced me that there is hope. We then founded nOffice as an additional structure, which concentrates on the built environment – architecture, urbanism, and landscape. Studio Miessen tends to be more engaged with research, writing, teaching, curating, and consultancy projects. Recently someone asked me whether the distinction is similar to OMA/AMO. It’s not. In fact it is totally separated in terms of the projects. However, there is a constant knowledge transfer and Studio Miessen tends to introduce clients to nOffice.

nOffice, Performa Biennial Hub, 2009, New York.

nOffice, Performa Biennial Hub, 2009, New York. Photo: Bradley Jones

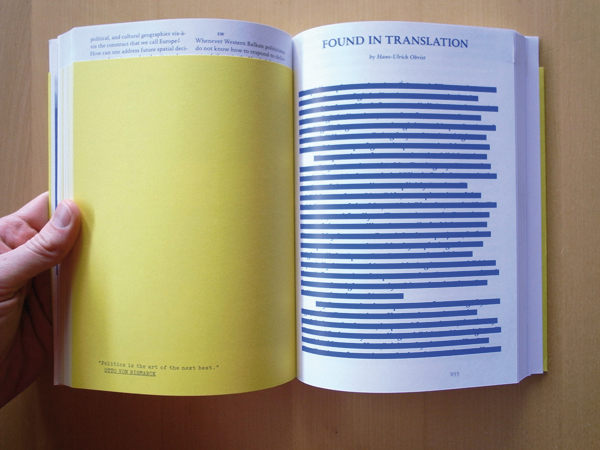

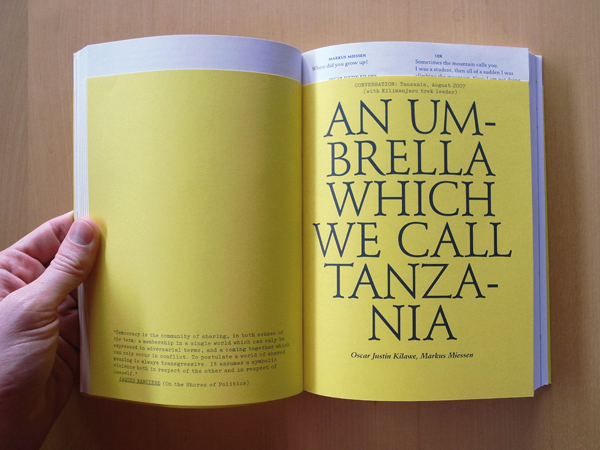

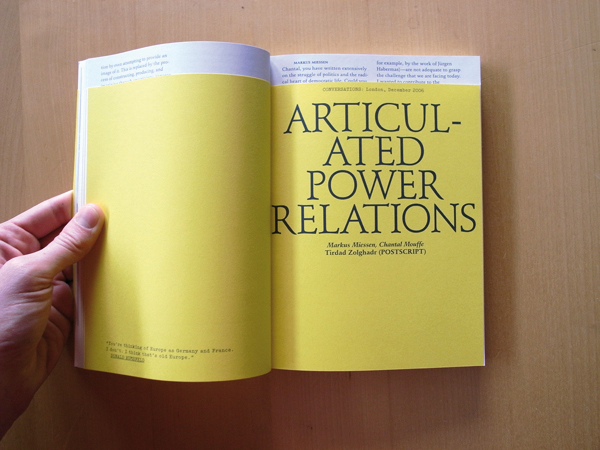

Markus Miessen, The Nightmare of Participation. Sternberg Press, 2010

Models for Tomorrow: Cologne, 2007, European Kunsthalle, Cologne. Project by: Nikolaus Hirsch, Philipp Misselwitz, Markus Miessen, Matthias Görlich

Markus Miessen, The Violence of Participation. Sternberg Press, 2007. Photo: Zak Kyes.

Markus Miessen, The Violence of Participation. Sternberg Press, 2007. Photo: Zak Kyes.

Markus Miessen, The Violence of Participation. Sternberg Press, 2007. Photo: Zak Kyes.

Markus Miessen, The Violence of Participation. Sternberg Press, 2007. Photo: Zak Kyes.